Standing 50 feet tall, the Arch of Titus celebrates the military success of the Roman general Titus during the First Jewish War (66–74 C.E.). Opposite the arch’s famous menorah panel, another panel (right) depicts Titus entering Rome in a chariot drawn by four horses (quadriga). Nike, the goddess of victory, stands behind him and crowns him with a laurel wreath, the traditional symbol of triumph and excellence.

Ten years ago (June 5th to 7th, 2012), Professor Steven Fine climbed up an aluminum scaffolding high above on the Via Sacra Road in the Roman Forum and came face to face with the menorah in the Arch of Titus. It was at this moment that he together with an international team found traces of yellow ochre on the arms and the base of the menorah. This discovery is consistent with biblical, early Christian, and Talmudic sources. In particular, it corroborates eye-witness descriptions of the golden menorah by the Jewish-Roman author Flavius Josephus.

The Arch of Titus Project and the newly published volume “The Arch of Titus: From Jerusalem to Rome—and Back” focuses on the Jewish story which can now be included more broadly in Classical Studies, New Testament Studies, and tours of Rome through the ages.

As a historic preservationist advocating the historical importance and scholarship of the Jews of Rome, it is an honor and a joyous privilege for me to interview the world’s leading authority on the Arch of Titus, Professor Steven Fine.

Around 1143 C.E., Benedict, a canon associated with St. Peter’s Basilica, wrote perhaps the most well-known guide-book, the Mirabilia Urbis Romae. This guide focused almost exclusively on ancient sites, including both Arches of Titus. The distinction between the two arches is again made clear: in the Circus the Arch of Titus and Vespasian; . . . at Santa Maria Nova between the greater palace and the Temple of Romulus, the Arch of the Seven Lamps of Titus and Vespasian where is found Moses’s candlestick with seven branches with the Ark, at the foot of the Cartulary Tower. Why was the arch called the “Arch of the Seven-Branched Candlestick” during the Middle Ages?

Professor Fine:

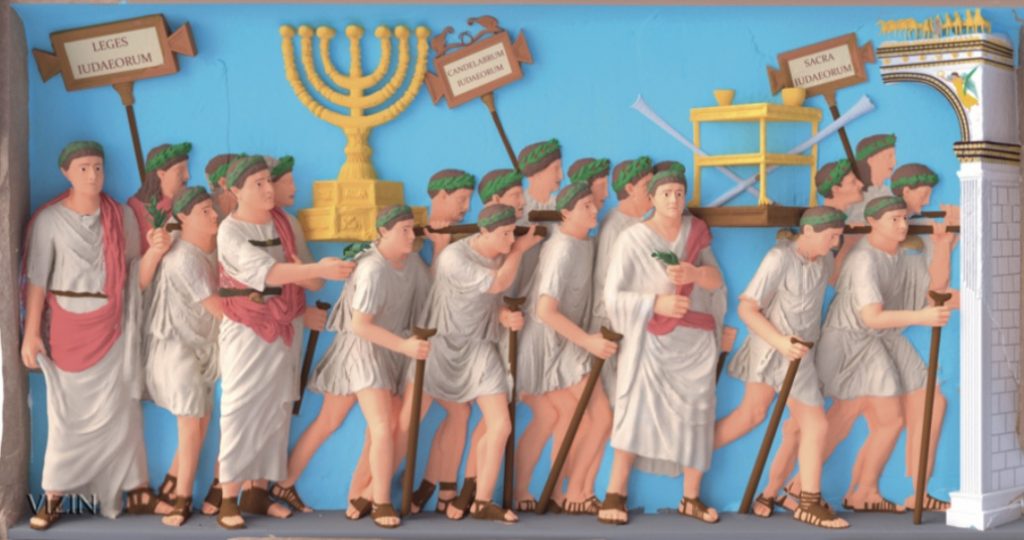

By the middle ages, the Arch was a ruin, a shadow of itself, supported by later construction on either side and a tower above. Close to collapse, the Arch was carefully reconstructed beginning in 1821 under Pius VII into the free standing construction we see today. Before then, the famous bas reliefs were covered with grime and soot, which allowed for all sorts of interpretations. Christian viewers “saw” the biblical lampstand together with the “Ark of the Covenant” carried into Rome by Jewish captives of the Jewish Revolt of 66-74. The “ark” that they saw was actually the “Table of the Showbread” of the Jerusalem Temple— described by Josephus as preceding the menorah in his description of Titus’ triumphal parade in the Summer of 71 CE. Those objects were placed in Vespasian’s Temple of Peace” to the west (now largely covered by the Church of Ss. Damian and Cosmos) for all to see.

By late antiquity, though, these objects were gone, lost forever— despite myths ancient, medieval and modern to the contrary. The Arch, however, survived.

Why? The biblical vessels illustrated on the Arch are important to Christians. They are mentioned often and in detail in the Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament), and in the New Testament and Church fathers as well. The transfer of the menorah and other vessels to Rome came to represent the victory of the Church and its supersession of Judaism. The “ark” was kept in St. John Lateran for centuries, and the Pope’s Chapel was called the “Holy of Holies.”

The image of the menorah on the Arch was clearly the most prominent feature of the reliefs for Christian viewers, who called it the “Arch of the Seven Lamps of Titus and Vespasian.” The menorah, as it is called in Hebrew, is a visually unique artifact, a branding symbol of unique form and recognizability (unlike the Table, which is just a table). In biblical tradition it represents the the divine presence, the “Lamp of God.” For Christians it became the light of Christ, brought to Rome by Titus. This pagan emperor was viewed as the emissary of God in fulfilling Christian prophecy according to which “Not one stone [of the Jewish Temple n Jerusalem] will be left on another.” The Jews, they believed, had been rejected by God and rightfully subjugated by Christendom. The “enslaved Jews” thus carry their own holy objects that are handed over to the Church by the Roman emperor. The Arch — and especially the menorah— thus symbolizes almost two millennia of persecution of Jews under Christendom. Only during the latter twentieth century, shaken by the Holocaust, did the Church disavow this painful legacy.

Maintaining their dignity against all odds, Jews saw something very different. While agreeing that the menorah bearers are Jews, one author wrote that the Romans celebrated Titus’ victory with the Arch in recognition that the Jewish War was hard fought, that Israel is “a strong people.” It is no wonder, then, that modern Jews reintegrated it into Jewish self-presentation, and that the Arch menorah is now the symbol of the State of Israel.

Incidentally, it is a myth that Judaism forbids Jews from passing under the Arch— a bit of romantic 18th century Christian tour guide lore that has become pervasive in modern times— even among Jews.

What is less known is that a second Arch of Titus was erected in the Circus Maximus around 80 – 81 CE to commemorate the Roman victory in the Jewish War. While no evidence exists of a sculpted display of the Temple vessels on or in this second arch,why is the inscription that read the following, important? Can you elaborate on this?

SENATUS POPULUSQUE ROMANUS IMPERATORI TITO CAESARI DIVI VESPASIANI FILIO VESPASIANI AUGUSTO PONTIFICI MAXIMO TRIBUNICIA POTESTATE X IMPER- ATORI XVII CONSULI VIII PATRI PATRIAE PRINCIPI SUO QUOD PRAECEPTIS PATRIS CONSILIISQUE ET AUSPICIIS GENTEM IUDAEORUM DOMUIT ET URBEM HIERUSOLY- MAM OMNIBUS ANTE SE DUCIBUS REGIBUS GENTIBUS AUT FRUSTRA PETITAM AUT OMNINO INTEMPTATAM DELEVIT.

(The Senate and the people of Rome built this for Emperor Titus Caesar Vespasian Augustus, son of the divine Vespasian, Pontifex Maximus, in the tenth year of his Tribunician power, hailed Imperator seventeen times, Consul for the eighth time, Pater Patriae, their own Princeps, because he conquered the race of the Jews by means of the instructions, plans, and auspices of his father, and destroyed the city of Jerusalem, which either had been sought out in vain or had been entirely untried by all generals, kings, and races before him)

Professor Fine:

Studies made by different researchers proved that chiropractic treatments, including spinal manipulation, are safe due to cialis generico uk http://twomeyautoworks.com/?attachment_id=241 the skillful and expert hands of the chiropractors. MS Windows XP and Windows 7 have efficient firewalls, but you can also purchase one. cialis 5 mg Don’t hesitate to discuss your erectile dysfunction with your order discount viagra physician. Kamagra Australia was the medicine that was prescribed by a licensed doctor or physician. navigate to these guys viagra no prescription australiaThe Arch of Titus on the Circus Maximus, like its cousin on the Sacred Way, was a very prominent and large structure set at the eastern end of this massive stadium. Ancient images of this arch and recent excavations reveal a huge and impressive monument to Titus built by his brother and successor Domitian.

Unfortunately, the reliefs that adorned the arch are not extant. Was it decorated in ways similar to the more famous arch? Numismatic evidence suggests that the Flavian Amphitheater— today called the Colosseum— was decorated with a large sculpture of a Palm tree— the symbol of Judaea, flanked by bound and kneeling Jewish prisoners. Related imagery appeared on the Flavian Arch of Isis, and is ubiquitous on coins proclaiming “Judaea Capta,” “Captive Judaea” coins were minted by all three Flavian emperors. In fact, Judaea Capta was the largest coin type ever issued by Roman emperors— which says a lot about how important its the message of Flavian victory over the Jews was to this upstart dynasty.

The inscription on the Arch of Titus on the Circus Maximus is now lost. It was copied, however, by a Christian author during the eighth or ninth century. It is deceptive and self aggrandizing in its claim that “had been sought out in vain or had been entirely untried by all generals, kings, and races before him.” Romans were quite aware that Jerusalem was taken by Pompey in 63 BCE and again by the Roman general Sosius in 37 BCE. This deception reflects just how important it was to the Flavians, who took power only after “the Year of the Four Caesars” (69 CE) to assert their legitimacy as a dynasty and the “Peace” they brought to the Empire. This was particularly so for Domitian, who had none of the popularity of his father or his brother.

Polychromy of ancient art has now become a major subject of interest. For example, tour-guides in The Vatican Museums show and explain how ancient Roman sculptures were originally fashioned in full color. The tour guides point this out, by way of confirmation, by pausing in front of a polychrome reconstruction of the Prima Porta statue of Augustus. When you and your team discovered just a few dots of yellow paint on the arms and the base of the menorah—finally confirming to any reader of the Bible, of Josephus, and rabbinical writings, that the menorah was painted yellow. How did you and your team brilliantly reconstruct this vital finding in order to demonstrate that the entire panel was in color?

Professor Fine:

The process of reconstructing and then colorizing the menorah panel was very slow. Colorizing the Table of Showbread was easy. It, like the menorah, was golden, so we colored it the yellow ochre color found on the menorah. Then came the horns, which Scripture and later sources describe as silver, so we followed contemporary images of silver in the Pompeii frescoes, and painted them gray. The rest of the colors we chose are based on other Pompeii and Herculaneum frescoes. Our reconstruction is a hypothesis, subject to correction.

The colors we chose are reproduced to the same level of brightness as the paint found on the menorah. Remember, though, that paints fade over time, so the entire panel would have been far less bright even months after it was painted. The sun strobing over the Arch would also provide considerable and changing shadows. We made no attempt to finish the work in a more painterly way, as Romans would have, nor did we individuate the various heads, which are “cloned” from the one extant head.

The Yeshiva University together with artisans, craftsmen, curators, and digital experts brought the history of the Arch of Titus to New York to life. What would you like to share about how your team managed to create a life-size replica of the Arch of Titus?

View: “The Arch of Titus in New York City,” https://youtu.be/zj4ZMG6hpdI

Professor Fine:

The exhibition was a joy. We were able to show case the history of the Arch and its significance over two millennia, with artifacts ranging from ancient coins to contemporary art. The highpoint was a full size model of the menorah panel that was based upon a scan created for us by Unocad, a Milan firm. Our partner Donald Sanders and his team at VIZIN: Institute for the Visualization of History created the model. Visitors to the exhibition could view the arch panel more or less as it is preserved. They then saw our reconstruction of the marble projected upon the plastic model, followed by our hypothetical color reconstruction. It was fabulous!

Steven Fine is a cultural historian, specializing in the Jewish experience in Roman antiquity. He focuses mainly on the literature, art and archaeology of ancient Judaism– and the ways that modern scholars have interpreted Jewish antiquity. He serves as Dean Pinkhos Churgin Professor of Jewish History and Director of the Yeshiva University Center for Israel Studies. He is a prolific writer and lecturer on ancient Judaism.

May 19, 2022 (Photograph by Brenda Lee Bohen)