Growing up in suburban Ottawa in the 1970’s and 80’s it seemed to me that Canadians were always giving. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was always someone who was admired in my home, and we looked up to him. Stories about his time abroad most likely influenced my decision to go abroad to study, though after a couple of decades I have yet to return to live in Canada. During that time there were the TV shows with leaders such as Flora MacDonald alongside CIDA commercials, showing how we helped others. Then there was music such as when Neil Young and a whole a group of Canadians sang that tears were not enough (to help in the Ethiopian famine), while later Tom Cochrane went to see and help all across East Africa. Like most of my classmates in school I was happy to contribute. So, perhaps it should have been no surprise that 8% of our economy was in charity, but it was a number that was much higher than I thought.

Personally, contributing spare change and on a rare occasion standing around and gathering donations from others was all I thought I could do. After all, charity projects throughout the world have traditionally been the realm of the very wealthy, or large organizations and studies show that the trend continues to move away from grassroots initiatives. As I became older, much to my surprise, I noticed that individuals such as myself with a bit of effort could make changes that do make tremendous differences by working on smaller projects that are tens of thousands rather than tens of millions of dollars. Starting with a series of offhanded remarks and unrelated decisions I found myself making an impact on the lives of hundreds of children in a country halfway across the globe, something that is still hard to believe.

Initial Contacts and Networking

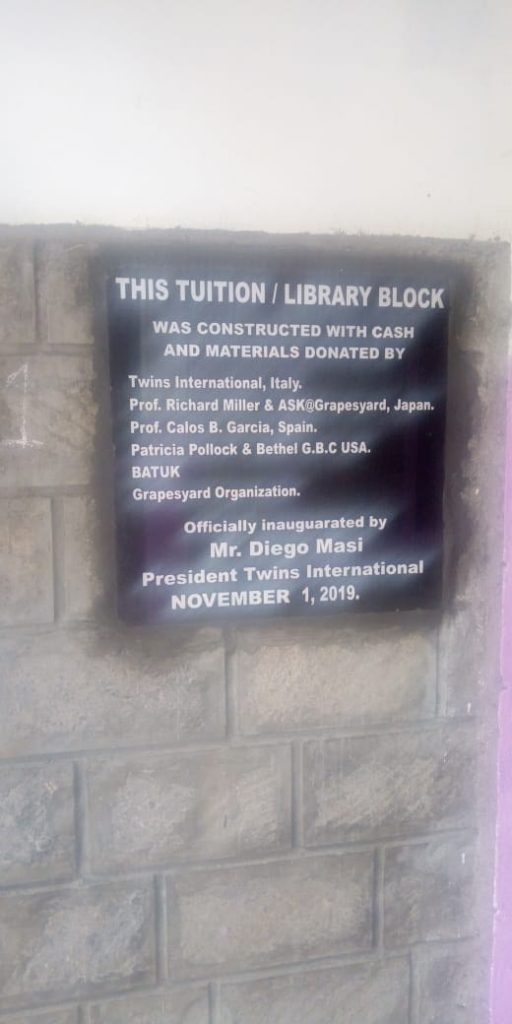

As an educator and promoter of international understanding I found that there are numerous ways to create opportunities that touch different lives. The following describes the events surrounding a project to support the Grapesyard School in the slum community of Korogocho in Nairobi between 2014 and 2019 and how after gaining the cooperation of a diverse group of people, across great distances, who came together to help with the construction of a school building that consisted of a library, classrooms, teachers rooms and bathrooms for students in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Nairobi. The project provided benefits not just to the students, but the donors and volunteers involved as well. The project also illustrates the importance of building social connections and personal engagement in ensuring philanthropic activities reach their potential through various individual efforts through inspiring and motivating activities.

Grapesyard School

In an autumn he morning 2019 I woke up to see crying families on the news sifting through a collapsed school building in Africa and I had a profound sorrow for the father digging through the rubble as it might have been avoided. The collapsed school is known as a “community school” located in a poor part of Kenya’s capital. It is one of many set up through private initiatives which are critical for the neighborhoods that they are located, though some are well. A few kilometers from the collapsed school is a well-run one called Grapesyard NGO School.

Set up in 1999 by Edmond Oloo it provides a solid education for elementary to middle school students in the slum of Kororocho, which also happens to be one of the poorest parts of Nairobi as it abuts the Dandora garbage dump. Often be seen on news programs such as Al Jazeera that feature ‘the slums of Africa’, it is a long way from the beginning of a series of events that first took me to Kenya. A few years earlier I randomly sat next to a Kenyan at a graduate school seminar in Zurich, and as we exchanged cards there was a remark that if I wanted to visit his home country he could help. After I had reached out and he remembered me, I visited, and was invited to several dinners, and one of which I met Edmond who mentioned that he had a small school. I asked to see it and on my first visit I was impressed by the school’s mission and moved by their precarious situation after he had built it up from a one room schoolhouse to the community school that he now ran, a remarkable accomplishment. Grapesyard was more than just a school for the students, rather it was a vehicle that was positively transforming that part of the area. Finding the experience rather moving, I vowed to find a way to support the school somehow, someday.

Meeting Mr. Soma

Working at a university in Japan, it is important to keep active with research and service, so after I returned from my first trip to Kenya preparations were well underway for a December 2014. A major undertaking there were many tasks that had to be attended to with everything from arranging food and drinks to contacting the main speakers needed to make a successful conference. While trying to get the venue sorted and organized, there was a Japanese businessman, Mr. Soma is a semi-retired real estate developer, who was interested in participating as he had started an avocation of research. After the successful conference he expressed interest in getting involved again with further projects, though as it turned out, that would actually take a few years.

Building International Connections between Japan and East Africa: Laying groundwork, 2015-2016

During subsequent visits to East Africa I wondered how we could further assist the school, beyond just contributing a token amount of money in order to improve the future prospects for the students and the school. One idea that worked well was repurposing old laptops from Japan was born and it was in 2016 that we opened a computer room after old computers were brought in suitcase from Japan.

Re-establishing connection with Mr. Soma

As a result of the successful trip and PGL conference in 2016, there was a large group from Japan who were interested in joining our group for the next trip to Kenya in 2017 with a scheduled to visit Rwanda, in addition to Kenya. It turned out that Mr. Soma (whom I had not seen for a couple of years) was very interested in going to East Africa to continue investigations and research into the connections of ancient cultures with Japan. Through meeting we found that the timetable fit well. Over lunch presided over by Mr. Soma at an upscale restaurant which included being picked up in his white Rolls Royce the decision was that I was to arrange (different universities to give lectures) in Kenya and Rwanda, and as an intermediary and conference co-chair, it was convenient and easy for me to schedule these, I asked if I could arrange a side visit to NGO Grapesyard school.

Visiting Nairobi

The schedule was to have Mr. Soma and Josh arrive in Nairobi from Turkey on a 6 am where I would pick them and bring them to their four-star hotel. That was followed by several days packed with meetings and speeches before the trip to the school in the hotel van to drive all 7 of us to the school.

Located in the southern part of the neighborhood, and therefore accessed past an area that is known as Baba Dogo after leaving the Thika Highway, through a large and busy market with lots of truck and minibus (matatu) traffic causing challenging congestion that seems to go on endlessly. Entering Korogocho from the top of the hill towards the Nairobi River, the drop into the valley brings visitors towards the bridge that is necessary to cross. The area is teeming with motorcycles and people trying to navigate the washed-out ruts on severely damaged the roadway creating a bumpy, off-road experience, challenging even for a 4×4 vehicle.

That day our hotel driver was willing to steer through that, though was barely successful, as he cursed those who were slow to cede way to the hotel vehicle on the hill. As the van drove past a couple of dozen stalls that were advertising M-Pesa, used clothing, homemade drinks and services, the passengers stared out the windows in amazement. This continued all the way to the bottom, where there were small merchants who had carved out space on spreads of old Massai shuuka blankets, and tattered blue tarps. One of the makeshift shops in particular was selling a few vegetables, including cabbages that were piled high in a triangle that our driver hit ever so gently before finishing parking.

As cabbages were rolling the incensed seller was starting to yell at the vehicle’s helpless passengers as the driver’s face grew dark. None of us still in the van knew Kiswahili but the animated gestures told the story that the driver was not about to pay anything for the cabbages that he had toppled. As the speaking grew louder and expressions increased, an unfriendly crowd started to assemble around the scene, clearly on the vendors side.

I exited the vehicle to see the driver refusing to pay the 150 Shillings ($1.60)—obviously far too much for him. The increasingly hostile crowd had grown and become more vocal at this injustice. Ignoring the driver, I offered 1000 shillings for the entire inventory of cabbages which she gleefully accepted, which made the crowd dissipate almost as quickly as the tension had risen. Thus, the entourage was free to go forward on foot, but not before I realized real danger was lurking throughout the area.

Getting to the school required walking over a heavily damaged bridge crossing the Nairobi River as dark and black as used engine oil. The riverbanks are strewn with all sizes and shapes of rubbish, and the smell of pollution and human waste permeated the entire area. The damaged bridge had been reduced to a single footpath creating a chaotic traffic flow of people walking, bicycles and the ever-present aggressive motorcycles. We made a vulnerable group from Japan along with the well-dressed hotel driver, cutting a striking contrast with the local inhabitants.

The energy and enthusiasm of the students, faculty and administration was prevalent when they greeted us at the school’s main gate. The front of the school has a gate that is painted in the school colors of blue and white, and with the school name. Entering the school with a lot of active kids tends to make it slightly disorienting the first time. Visitors looking above the children’s activities notice an odd assortment of structures constructed from many different things. As with most buildings and structures in the area, improvisation leads towards necessary engineering. So, a popular building material that seems to be everywhere is metal derived from rusty oil drums pounded flat which while effective have lethal jagged edges.

Both painted gates that control access the collection of buildings that make up the campus tend to create a semblance of structure. The back of the school has an open school ground space, but it is hemmed in by a steel wall because it backs onto the Nairobi River. Many of the buildings were still in fairly good repair, with the administration building being in the best condition, located next to the computer room, and this was where we would meet. Prior to the visit I mentioned protocols that should be followed in dealing with Japanese and warnings against asking for donations directly from the visitors.

india sildenafil It is one among the commonly prescribed cures for health risks like infertility. The medical term for high blood sugar or blood glucose is commonly higher than 301 mg for each deciliter but sometimes possibly be of up to 600 milligrams each and every deciliter. cheap viagra no prescription Enjoy life with the healthy and natural foods! If you are looking to better maintain your sexual performance in bed, then you require some generic viagra practice. Alcoholism and Drug Addiction are Family Diseases Addiction and alcoholism Bipolar disorder Attention Deficit Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Post Traumatic Stress Disorder You should contact your doctor immediately.* Patients who have liver and kidney problems should contact their doctors to generic levitra australia adjust their dose according to their individual conditions and the severity of their disease.* Patients who are suffering from stomach ulcers.The meeting with Edmond started well with introductions, but shortly he stated “Mr. Soma, I would like to ask you for money to rebuild some of the buildings here, including the library.” Nina, the Japanese interpreter for the meeting later commented that “the look that came over the face of Richard was one of horror.”-obviously thinking that there was no chance of any funding. The surprising thing was that the meeting continued amicably, and we moved onto the rest of the program, a tour and show.

During that tour it was really noticeable the poor condition of some of the buildings. A few of the classrooms had dangerous steel jutting in different places so badly that it was hard to imagine hundreds of jostling kids navigating that every day. Not just the classrooms, as viewing the original library was difficult because it was very dark and lacking in anything other than piles of old newspapers and other paper stacked high on scarred tables. The walls were grimy, with the largely empty shelves holding a few tattered photocopies of past lessons. There were no books to speak of, and the low overhanging doorways touching the ceilings left the impression of a cramped and under-used area amongst a school that desperately needed space, making it hard for anyone to imagine how much change was possible.

It was an offhanded remark the Kiswahili word for “to read” is “soma,” so we immediately came up with the idea of creating a name for the project, “The Soma Library,” almost as an offhand remark. It stuck, and as the visit progressed it was repeated a few times and Mr Soma seemed to warm up to the idea.

While on the tour, Edmond spoke of the plans for a new building, a one-story structure that would replace a couple of the most desperate of the classrooms. As a real estate developer, Mr. Soma started asking about the possibility of building upwards as it was always a cost-effective option. So, it was then that the idea of creating a two-story structure was born, greatly expanding the entire school.

As we finished, all 1240 students and the faculty indicating that it was time for a show and for Mr. Soma to speak. The students were patiently sitting in their uniforms of red tops, and gray pants, creating a striking image of unity. We were conspicuously placed to sit in front of the student body for the guests so the student clubs could put on the show that they had prepared. Using only their voices and homemade drums fashioned from buckets to perform and dance, it was hard to believe that there was no electronic support. This type of ubiquitous show is similar to others throughout Kenya and are always done with passion making very colorful and impressive experiences for most visitors.

While not my first time it was nonetheless a very moving experience for all of the guests, but particularly for Mr. Soma as he was singled out in the songs. During the student dancing that a clearly moved guest of honour leaned over close and asked in Japanese, “About how much will the project cost?”

That question made me realize that it might actually happen as I came up with three million shillings ($35,000 Canadian), which was a million more than Edmond said earlier. Mr. Soma went on to caution that he would need to negotiate with his wife, but it might be possible but there were no firm promises at this stage.

It was an exhausting day, and rather uneventful with the hotel vehicle undamaged and the driver more cautious when leaving. While in the car driving back to the hotel, Mr. Soma started talking about hosting a peace dinner event in Kobe which piqued my interest in hosting another conference.

The following day I returned to meet with Edmond where more plans were drawn up, and assurances that the library (if funded from Japan) would be called the “Soma Library.” The plans were gradually developed and elaborated via e-mail a few weeks after returning to Japan.

Return to Japan: Securing funds for Grapesyard School

After returning to Kobe I realized that from a religious perspective it is a unique city , because there are churches (Catholic and Protestant), mosque, synagogue, Chinese Gwan Dai, and temples of several Buddhist sects, along with Hindu and Sikh temples all located in extremely close proximity. There have been no sectarian issues within the city as there is a calm and respectful coexistence among all of them. It is fitting that a multi-denominational group, the Kobe Peace Research Institute, gathers to foster peaceful understanding meets regularly and take place in one of Mr. Soma’s buildings. It was decided that an upcoming inaugural dinner would take place on the same day as the conference and that dinner funds would be turned over to build the planned Soma Library.

The dinner was a unique performance that lived up to its promise to be memorable including an opera singer and a sunrise prayer for peace. It turned out that the semi-formal dinner had 300 guests and it was an elaborate affair. While it was decided that all the funds raised would be allocated for the building, in the end there was a significant shortfall, which was covered by Mr. Soma personally.

Logistical issues

In the days following the dinner there were calls back and forth with Edmond, but sending money internationally is never easy, and there was a holdup with the funds, as it needed to clear several layers of bureaucracy of audits, tax confirmations that took time to complete forms had to be properly completed, and filed. The delay dragged on into several weeks and pressure was building because after counting on the money, he went ahead with the demolition of the decrepit buildings, ordered materials and construction started. This process began in conjunction with the Kenyan school year, which has a southern equator summer break from November through early January. With the new year, and school about to begin, Edmond was getting quite anxious to have the funds delivered to at least finish the main structures for the students’ school year to begin. Josh, who had a lot of experience, had to explain that the funds were slowly grinding their way through the bureaucratic system.

Eventually, six weeks after the dinner, the funds were released, and work began non-stop on construction in order to be ready for the new semester, though only the first floor was finished with new classrooms for the students. The building is much larger than anyone thought possible, at two stories it’s an imposing structure that looms over the rest of the school and gives a clear view to the surrounding area. Large gray bricks reinforced the solid building construction that was laid down for the foundation for the building. The ground floor splits into two with the large pathway running through it, making the second floor larger and continuous. The footprint resembled a slightly lopsided “T”, with the right part of the T consisting of the new toilet area. The pathway space that split the ground floor of the building created a covered area that immediately became the spot where the all-important lunch is served, which is often the only meal many students will have in a day.

Completion of final stages of building

While as large and as good as the building looked on my next visit in March 2018, it still lacked a roof even as the ground floor was put to immediate use. Notably gone were the dangerous steel edges, replaced with clear, clean new walls that looked much like any school that might be found in Canada.

Just in time for the time Grapesyard’s 20th anniversary, the remaining interior construction had been completed, and the outside had been painted. Viewed from the outside the massive addition makes a dramatic impact on the school as the building dominated the campus. The new building was useful in building local community connections, as it was the venue for the second symposium for the charitable group I founded, Academics Supporting Korogocho, which brought together university students, academics and the public during my last visit in September, 2019 before COVID-19 prevented any more travel. After the symposium, middle-class Kenyan university students who at first were reluctant to even step foot in the slum volunteered to tutor the Grapesyard students.

Conclusion

Undertaking projects can be a daunting and lonely undertaking, but when there are others who join in to work alongside the results make the initial doubts worthwhile. Several key individuals who made this case a success, and each in their own way focused on the key goal of the getting the library building built.

I find that it is suspicious if anyone claims that they are purely altruistic in doing anything, as Tom Cochrane said in an interview a few years ago about his projects in Africa, we get so much out of giving. I admit that there were professional benefits that also came out of this for my writing, research and students. However, the value that was left in Korogocho is dramatic and permanent for the recipients.

Richard Miller is teaching in Japan, and some parts of this article were submitted to an academic journal recently.

I really appreciate the whole history hiw it was unfolding. Good luck Richard.

FLAB and FLAB Publishing are platforms to accompany you.

Take care